After completion of this chapter the participant should be able to:

| An infant who has signs of severe respiratory distress requires oxygen. |

|---|

|

The NYI requires oxygen, if oxygen saturation is less than 90%.

Normal oxygen saturations (SpO2) for neonatal patients should be:

NB neonatal patients should reach oxygen saturations of 90 – 95% by 15 minutes after birth.

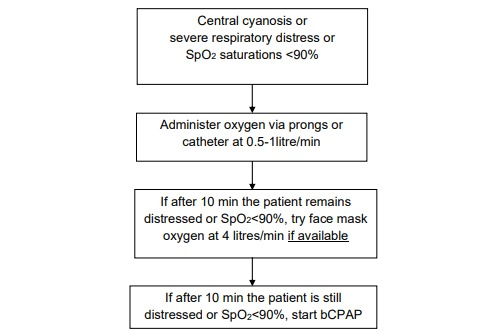

If there is severe respiratory distress, SpO2 readings are less than 90% or there is central cyanosis the patient should be commenced on supplemental oxygen therapy.

The source of oxygen is generally the oxygen concentrator but may also be an oxygen cylinder. Oxygen is administered preferably by nasal prongs, but if unavailable nasal catheters can be used. If higher amounts of oxygen are required face masks can be used.

A baby with cyanosis or severe respiratory distress should be allowed to take a comfortable position of his choice and should be given oxygen immediately via nasal prongs or catheter. Escalate the oxygen therapy in a stepwise fashion depending on need and availability.

If the baby’s breathing difficulty does not improve on prongs or catheter oxygen, despite increasing the flow:

Place the YI on oxygen at a high flow rate (4 litres/min) via face mask if possible or if this is unavailable, or if the breathing difficulties persist, then place the baby on bCPAP.

Monitoring and ongoing care of the patient:

(Teach the mother to help her baby by also looking out for the following problems):

If breathing difficulty is so severe that the baby has central cyanosis even with high flow oxygen or bCPAP, or the work of breathing increases despite increased oxygen delivery, rule out a pneumothorax clinically or with a chest x-ray. Discuss with senior or colleague.

Once patients can maintain normal oxygen saturations and are clinically stable, the oxygen flow rate should be reduced in a stepwise manner, based on clinical response:

Once oxygen saturations are consistently above 95% at 0.5 L/min and the patient is clinically stable, remove oxygen from the patient by gently removing the tape and taking the prongs out of the patient’s nostrils.

Recheck the saturations after 15 minutes.

Where pulse oximetry is not available, the duration of oxygen therapy is guided by clinical signs. If oxygen saturations are not available, the oxygen can be stopped if the baby does not have respiratory distress,(i.e., no increased work of breathing, no increased respiratory rate, and baby not tiring), but keep under review and recommence if the respiratory distress increases after stopping the oxygen.

Avoid prolonged SpO2 > 96% in premature infants as it can cause damage to the eyes (retinopathy of prematurity) leading to blindness, and can cause damage to the brain and the lungs. Premature infants should have oxygen saturations kept within 90-94% when given supplementary oxygen or CPAP.

Sources and delivery methods of oxygen

See supplement on oxygen concentrator module.

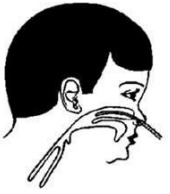

Take care that the nostrils are kept clear of mucus, which could block the flow of oxygen.

A flow rate of 0.5-1 litres/min will deliver 30-35% oxygen concentration in the inspired air

Aim for oxygen saturations >92%.

Nasal tube or catheter: Use 8 French size catheter. Determine the distance the tube should be passed by measuring the distance from the side of the nostril to the inner margin of the eyebrow.

Gently insert the catheter into the nostril. A flow rate of 0.5-1 litres/min in infants will deliver 30-35% oxygen.

Aim for oxygen saturations >90%.

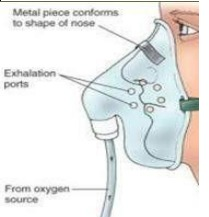

A simple face mask will deliver 40-60% oxygen in an emergency and if the infant is very distressed.

A minimum of 4 litres of oxygen per minute is needed to prevent rebreathing of expired air.

A face mask with a reservoir attached will deliver 100% oxygen. It may be used for resuscitation.

The problem with this method is that it may require one concentrator per NYI, which may be challenging if several NYIs require oxygen at the same time.

Aim for oxygen saturations >90%.

Oxygen sources may be used to provide supplemental oxygen directly to patients, shared between patients by using a flow splitter or used with other treatment devices such as continous positive airway pressure devices.

Supplemental oxygen is indicated for sick children, especially those with hypoxia. Hypoxia is defined as an oxygen saturation (SpO2) < 90%. See oxygen therapy for more information.